ENGAGE Stakeholder Dialogue (Latin America/Brazil)

April 19-20, 2022

The ENGAGE series of stakeholder dialogues continued in April 2022 with an online meeting on decarbonization pathways in Latin America and Brazil. The meeting was organized in 4 sessions and discussed modelling results, the feasibility of rapid decarbonization and a broad range of issues related to burden-sharing. With a total of 53 stakeholders and ENGAGE partners from all work packages, the presentations, discussions and surveys carried out during the meeting brought up key issues with respect to the achievement of decarbonization goals that are also relevant for future research.

Starting with a short presentation by Joeri Rogelj about the term “net-zero” and the importance of being clear about whether we are talking about “net-zero carbon emissions” or “net-zero greenhouse gas emissions”, the first session then focused on modelling results on decarbonization pathways in Latin America and Brazil. The focus of the presentation by Roberto Schaeffer was a scenario in which global CO2 emissions achieve net-zero in 2060. This allows for higher CO2 emissions globally until 2050 but thereafter carbon dioxide removal technologies are required if the Paris goals are to be achieved. The modeling results, based on a global and national (for Brazil) “least-cost” logic, show, however, that while global emissions reach net-zero CO2 in 2060, Latin America reaches net-zero CO2 emissions by 2040. This is achieved, for example, through a very large increase in the share of renewable energy in total primary energy supply.

These results were discussed in breakout groups. Key points raised in these lively discussions were:

- Extra efforts and political will are necessary in order to develop consistent climate policy, regulatory advances and long-term strategies. Each country in Latin America faces different challenges in this respect. Political will would be strengthened, if there were a critical mass of people asking for change. For implementation of decarbonization pathways, access to information, data and good practices is needed. International cooperation, finance and responsible carbon markets would support the transformation to net-zero CO2 emissions. Furthermore, it would be important to align national and subnational initiatives, as well as public and private (civil society and business) initiatives.

- There are many reasons why a systems approach to tackling the challenges of decarbonization will be necessary. For example, a major transformation of the food system in Europe would have implications for food production systems in Brazil. Similarly, decarbonization of industry in Latin America depends in some sectors on international demand. The necessary sustainable transformation of land use also requires a systems approach.

- In Latin America agriculture is a major sector of the economy, causing high emissions levels through, for example, livestock herding and deforestation. In the short term, there is an absence of policies to deal with these emissions.

- In many cases, the necessary technology is available but implementation and upscaling are needed. The upscaling is constrained by a number of factors, including the attitudes of managers in business and industry and of government decision-makers, the suitability of buildings for solar panels, the hilly terrain making it difficult to switch to electric vehicles. While a greater shift to biofuels would support decarbonization, transport does not receive significant attention in Latin America.

Session 2 started with a presentation by Aleh Cherp on empirical studies of the feasibility of decarbonization pathways. These studies look at historical and other evidence to see whether transitions required to meet climate goals are feasible. The empirical evidence shows, for example, that the rate of decline of fossil fuel use required for the years between 2025 and 2035 in some decarbonization pathways is unprecedented. The empirical evidence not only provides indications of the potential feasibility of decarbonization pathways, it also provides insights into the mechanism of transitions. After the presentation, breakout groups reflected on what they heard and discussed the particular challenges that Latin American countries face in meeting climate goals. The participants noted the importance of feasibility assessments to support discussions between researchers, civil society and other stakeholders. Further key points were:

- For Brazil, the presentation shows that feasibility of decarbonization has increased; parts of the needed transition are happening automatically, however awareness of the problem and challenges is still not enough and illegal deforestation continues on a large scale.

- Mobilization of finance is needed to develop the biofuel/biomass/food industry in Latin America. Often incentives, external political pressure and knowledge exchange on sustainable practices are the key factors that foster sustainable development in small countries.

- Trade could be used to increase the feasibility of sustainable land use, if there were mandatory certification schemes, for example, to ensure that products for export were produced without deforestation.

- Engineered solutions require long-term strategies that oftentimes cannot be provided by autocratic regimes.

- In Latin America, it is important to recognize the historical importance of social movements and social engagement in pushing for actual changes. The implementation of ambitious decarbonization pathways is less a technical issue and more a social and political issue. Public and political perspectives often differ.

- The Russian-Ukrainian war may have an impact on feasibility due to the increase of the price of oil. If the prices remain high, there could be reluctance to move away from oil and gas.

Session 3 of the workshop focused on the multidimensional feasibility assessment of decarbonization pathways. Elina Brutschin presented the online tool developed in the ENGAGE project to make such assessments and to enable a more interactive engagement with scenarios. The tool is based on an operational framework that allows a systematic assessment and comparison of scenarios along key dimensions of feasibility identified in the 2018 IPCC Special Report. The dimensions of feasibility considered in this assessment tool comprise geophysical (e.g., the potential availability of solar or wind energy), technological (e.g., the availability of renewable energy technologies), economic (e.g., the carbon price or stranded assets), socio-cultural (e.g., dietary change) and institutional (e.g., institutional capacity to implement rapid decarbonization) concerns. Rather than making claims about which pathways are feasible or not feasible in the real world, the framework allows the identification of trade-offs over time and across dimensions. The tool allows systematic mapping out of areas of concern and highlights the enabling factors that can mitigate them. After the presentation, Elina Brutschin presented a survey in which participants were asked to give their opinion on the levels of transformation that could be achieved in Latin America by 2030 for 4 key indicators: the share of non-biomass renewables in electricity generation (%); the share of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies in total electricity generation (%), carbon price levels, and final energy demand levels. The results of the survey were used in the online multidimensional assessment tool to show participants how their assessment affects the feasibility evaluation of decarbonization pathways to achieve the Paris 1.5o C goal.

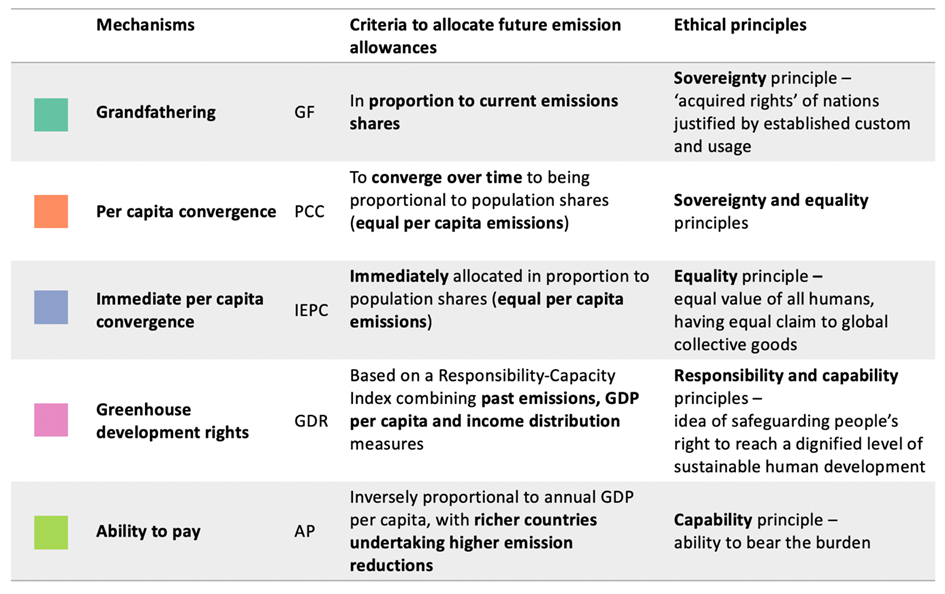

The final session of the workshop focused on how the challenges of rapid decarbonization can be shared in a fair way. Zoi Vrontisi presented the different principles (see Table 1) that can be used to share the challenges: grandfathering, per capita convergence, immediate per capita convergence, greenhouse development rights and the ability to pay. These principles can be implemented through policies on the domestic or international level or in a hybrid scheme combining action at both levels. The presentation showed examples of greenhouse gas emission pathways in different regions using the different principles. Depending on the equity principle chosen, the greenhouse gas reduction effort, economic implications and carbon price differ across regions. After the presentation, Silvia Pianta introduced a short survey, in which participants were asked to select their preferred equity principle. Since the survey also showed some of the modelled consequences of the selected principle, it was also possible to change the selection. The results showed a strong preference for Greenhouse Development Rights, which is based on the ethical principle of safeguarding people’s right to reach a dignified level of sustainable human development. The survey and presentation led to further discussion on important points of relevance for further research and for policies to share the challenges of transformation to a low-carbon economy:

- The terminology must be clear and used carefully. “Burden-sharing” has a negative connotation. The principles are not necessarily about equity, so perhaps the term “ethical principles” might be better.

- A rights-based approach anchored in law provides many opportunities. However, there is concern about the conditionalities applied to financing for developing countries.

- When thinking about Greenhouse Development Rights, care must be taken not to assume that development should take place as it has in the past. The paradigm of “development” has to change, to align with the global climate and sustainable development goals.

Table 1. Description of climate mitigation effort sharing principles.